January, 1977 Corgi Books

(Original UK hardcover edition 1975)

Well, the Internet Archive fixed itself and this final volume of the Shaft series, only ever published in the UK, is now back online. A big thanks to the person who scanned and uploaded their precious hardcover copy, as The Last Shaft is incredibly scarce and overpriced, either the orginal 1975 UK hardcover or the 1977 Corgi paperback. It’s surprising the novel still hasn’t been published in the United States.

And also a big thanks to Steve Aldous, who notes that Shaft creator Ernest Tidyman intended this as the final novel in the series from the outset, and tried to get it published in the US. I’d love to know why he was unable to; it sounds as if Tidyman was courting upscale (read: hardcover) imprints, which is odd, given that the previous two Shaft novels – Shaft Has A Ball and Shaft’s Carnival Of Killers – were paperback originals. Had Carnival Of Killers and Shaft Has A Ball sold so poorly that Bantam passed on The Last Shaft? Or was it that Bantam (or other US imprints) passed on The Last Shaft due to Tidyman’s insistence on making the title of the book literal? I guess we’ll never know.

The helluva it is, Shaft’s Carnival Of Killers is the book that should’ve been passed on in the US, with The Last Shaft coming out instead. Carnival Of Killers, written by Robert Turner, was incredibly tepid, whereas The Last Shaft, written by Philip Rock (who turned in the awesome Hickey & Boggs tie-in), is for the most part fantastic – a pulpy slice of ‘70s crime, served up just the way I like it. And Philip Rock is a much more talented author than Robert Turner; there is no part where Rock seems to be winging it, banging out the words to meet his quota. The Last Shaft moves at a steady clip throughout, maintaining tension, characterization, and good dialog. In fact it comes off at times like Hickey & Boggs, which itself was a fantastic piece of ‘70s crime-pulp.

There’s no pickup or mention of the previous book, Shaft’s Carnival Of Killers. Shaft is even more bitter and worn-down when we meet him this time, looking out the window of his Manhattan apartment in the very early morning hours and wondering if he wants another belt of vodka. We are told Shaft is sick of New York, and wonders if it is time for him to go. Philip Rock maintains the world-weary characterization of John Shaft that Ernst Tidyman gave the character, as Robert Turner also did, but Rock manages to make Shaft likable, whereas Turner didn’t. Also we are often told Shaft’s a big bruiser, and, given the amount of action in The Last Shaft, I more so saw Jim “Slaughter” Brown as Shaft than I did Richard Roundtree.

But then, The Last Shaft could just as easily have been the novelization of the third Slaughter movie we never got. It has more in common with the Blaxploitation action movies of the early-mid ‘70s than it does the hardboiled P.I. yarn Ernst Tidyman gave us in the original Shaft novel (which I really need to go back and read to completion someday). In this one we have Shaft beating people up, gunning them down, blasting away with a machine gun, and even blowing a place up and napalming stuff. We’re often reminded how he’s “Big, Black, and Bold,” per Billy Preston’s awesome “Slaughter” (which curiously was never released in its complete form until 2009’s Inglourious Basterds soundtrack.)

Overvall, The Last Shaft sees John Shaft essentially becoming another Executioner or Revenger, or any other of the proliferation of mob-busters who showed up on the paperback racks in the mid-‘70s. Which again makes it curious that this novel did not come out as a paperback here in the US. Regardless, Shaft here turns into a one-man commando squad who takes on the underworld, even outfitted with a trick vehicle that’s stuffed to the gills with all manner of firearms and explosives. He even manages to get laid while kicking some Mafia ass, which is also par for the course for these ‘70s mob-busters.

The plot is basically a Maguffin that allows Shaft to become a vigilante. He gets a visitor despite the early morning hour, none other than Captain Vic Anderozzi, a recurring series character. Anderozzi has come here with a guy named Morris Mickelberg, who per Anderozzi is the guy responsible for all the payoffs and whatnot going on in the city. Anderozzi has also brought along a massive box that contains all the dirty secrets – names, payoff dates, receipts, etc. It’s kind of a goofy setup, but Anderozzi’s reasoning is that Shaft is the only guy he can trust – the captain’s goal is to take Mickelberg and the box to the District Attorney first thing in the morning, and he just needs someplace safe to stay in the interim.

Shaft’s reaction makes him seem a wholly unattractive character, which gave me bad flashbacks to Shaft’s Carnival Of Killers. Shaft essentially tells Anderozzi he’s crazy and immediately grabs a shotgun and takes off – Shaft realizes “half the city” will be out to kill the captain, kill Mickelberg, and get that box. So Shaft leaves his “good friend” in the lurch, but to Shaft’s credit he has a change of heart while escaping; Shaft sees two men on the roof of his apartment building, one of them wielding a machine gun, and he swoops in to the rescue. As mentioned, Shaft does a fair bit of killing in The Last Shaft, blasting these two would-be hitmen apart with his shotgun. Philip Rock doesn’t dwell much on the gore, but he capably handles the action, a gift he demonstrated as well in Hickey & Boggs.

Ernst Tidyman foreshadows his intention of making the title of The Last Shaft literal with the offing of a major character here in the opening, an occurrence which sends Shaft on his rampage – and furthers the “one-man commando Mafia buster” connotations of the novel. (I say Tidyman and not Rock, as per Steven Aldous the novel is based on a storyline Tidyman gave to Rock, with Tidyman also editing Rock’s final draft.) This death serves to be Shaft’s impetus for the rest of the novel: to get revenge on the killers and see that they all burn, handing off Mickelberg’s papers to the proper authorities. But Shaft is from this point a hunted man, with assorted crooks, mobsters, and corrupt cops out to get him.

If there’s any failing to The Last Shaft, it’s that Rock (and Tidyman, I guess) introduces a deus ex machina conceit, a character who is randomly introduced into the narrative and will prove, again and again, to have just what Shaft needs for any given situation. This character is named Willie, a seemingly-inconsequential character who is introduced when Shaft checks himself into a hotel in the city. Willie, we’re told, has a “peculiar face,” one that is “striated,” and his hair is goofy, too. Another character mentions that Willie’s wife works at a salon and she “experiments” on Willie for practice. It’s an altogether curious intro for a character who will ultimately play a huge role in The Last Shaft, indeed serving as Shaft’s sidekick. Again, one can see this as a novelization of a movie that never was.

Willie, as it turns out, is aware of who Shaft is (our hero giving a fake name when checking in and also covering himself with a hooded parka), and offers his help. This begins a gag that runs through the novel; Willie has decided he wants to be a private eye, and has been taking correspondence courses on it. But as the novel progresses, it turns out to be more – much more – than this. Willie not only knows all the tricks of the trade, but also has a delivery truck that is outfitted with virtually every firearm (up to and including machine guns), a mobile phone, and even C4 plastic explosive. (Not to mention napalm!) Rock clearly knows all this is a bit too much, and to his credit he has Shaft initially shocked by this, until finally accepting all of Willie’s vast bag of tricks with nonchalance.

But seriously, if Shaft needs to shoot at someone, Willie has a machine gun for him. If Shaft needs to get some people out of a building they’re holed up in, Willie has napalm for Shaft to douse the parking garage with, flame-roasting the people within. (A sequence that has an eerie bit of prescience to it; Shaft and a random New Yorker stand on the street and watch the building burn, wondering how long the people trapped above have to survive, much as real-life New Yorkers would 26 years later as they helplessly watched the Twin Towers burn on 9/11.) If Shaft needs to do some detective work and get a phone number, Willie knows just the things to say to the operator on his mobile phone. And yet at the same time we are to understand that Willie is naïve, an amateur who looks up to Shaft; there’s a big of a Hickey & Boggs vibe here, with the bickering and bantering black-white duo, but Willie is not Shaft’s equal on the action front, and acts more as the straight man.

Willie also acts as a chaffeur, driving Shaft around town in his delivery truck, which is disguised as a bakery truck. And if that disguise is uncovered, not to worry; Willie has also taken a course on how to quickly paint the truck so that it looks like something else, like for example a yogurt delivery truck. Meanwhile Shaft sits in the back of the truck, formulating his plan of action; the second half of the novel is comprised of a series of assaults Shaft stages on the New York underworld, again operating in the same capacity as a Mack Bolan or a Ben Martin – like Bolan, he even takes to calling his targets moments before hitting them.

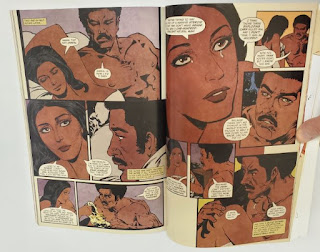

Shaft also finds the time to pick up Sandra Shane, Morris Mickelberg’s hotstuff ex-wife, a former topless dancer Mickelberg picked up years ago. Now she’s determined to get the money her ex never gave her, becoming sexually excited over Shaft’s promises to get it for her. Rock doesn’t do as much to bring her to life, but at least Sandra Shane provides the series with some genre-mandatory spice, something that was completely absent in Shaft’s Carnival Of Killers. That said, the Shaft-Sandra conjugation is not much dwelt upon, though we learn that Shaft, uh, gets hs rocks off a few times. Our author has more fun with another secondary character, Rudolph Gromyck, a dirty New York cop who tries to outwit the Mafia and his fellow cops and find Shaft – so he can get Mickelberg’s papers and become rich off them.

There are a lot of one-off mobsters yammering at each other on the phone before getting blown away by Shaft; our hero kills a fair number of people in the novel, again like Bolan or any other ‘70s men’s adventure protagonist. Rock also provides a little comedy with Willie fretting over Shaft using all those weapons in his truck – goofy, particularly when you consider that Willie himself is the one who stocked his truck with all of the weapons. But given that the novel moves so quickly, the reader doesn’t have much time to ponder over all of the plotholes.

Unfortunately, the reader does have time to ponder over the ending of the novel, which is guaranteed to upset everyone. SPOILER ALERT, but The Last Shaft, as mentioned, lives up to its title. In a humorously tacked-on ending, we read as Shaft finally returns to his apartment building after successfully wiping out all the criminals who have been hounding him the entire novel. And on the way into the building the poor guy is mugged by a random thug and shot dead. This brief sequence, likely written by Ernest Tidyman himself, does not flat-out state “Shaft died,” but otherwise it’s clear as day – the mugger shoots, and we’re told the metal of the gun “became a blossom of flame…but only for the shortest moment known to man, that moment before dying.” Granted, the character dying could be the mugger; Shaft has already proven himself to be quite a resourceful individual, and might have pulled out a holdout gun and shot the mugger before the mugger could shoot him. I mean, Tidyman (or Rock) doesn’t specify who is dying in that last sentence, so it might not even be Shaft. And yet, I don’t think so; Tidyman’s intended irony here is that Shaft has spent the entirety of The Last Shaft cleaning up the city – of the bigwig mobsters and other high-level crooks – and then he is shot down by a random mugger.

As mentioned above, perhaps it’s this lame ending that kept The Last Shaft from being published in the US. If so, it’s strange…I mean the publisher could’ve easily removed it before publication. As I say, this brief finale is tacked on, and comes off as the literary equivalent of the similarly tacked-on surprise ending of contemporary action flick Sudden Death: a downbeat, nihilistic cap-off that seems thrust on the reader more so for shock value than for any dramatic intent.

Overall, I did enjoy The Last Shaft, and it’s too bad Tidyman didn’t get it published in the US…and change the finale along the way, opening the series up to be the continuing adventures of Shaft and Willie. But likely Tidyman considered himself above such pulpy things, and preferred offing the character that had made him famous.

I’m reading the Shaft books way out of order; next I will likely read Shaft Has A Ball, but one of these days I will read Tidyman’s original Shaft novel.