Jim Kelly movies:

Black Belt Jones (1974): This was to be Jim Kelly’s big role after his starmaking turn as Williams in the previous year’s

Enter The Dragon. Robert Clouse again directs, but this time the film is a

Blaxploitation joint with a comedy overlay. It’s still the ‘70s, though, so there’s a bit of blood at times and some random nudity. Oscar Williams handled the script (as he would for the execrable sequel, more on which below), and it seems like a clear attempt to launch Kelly as a new urban action hero. I believe

Black Belt Jones did fairly well, but as it turned out this would be the only time Jim Kelly would carry a major studio film.

As a kid I was of course familiar with Kelly, having first watched

Enter The Dragon as a teen, but I didn’t discover

Black Belt Jones until the summer of 1994, when I was 19 and came across the video in a Suncoast Video store (remember those?). To say this movie had an impact on me would be an understatement. Actually – it would be the

theme song by Dennis Coffey (miscredited as “Dennis Coffy” in the closing credits) that had the biggest impact on me. I would watch the video just to hear the “Theme From Black Belt Jones,” and even recorded it directly onto audio tape so I could play it. I even did dumb faux-movie commercials in the campus studio and would use Coffey’s theme song on the soundtrack. As far as I’m concerned, this unjustly-overlooked track is the best song in the entire Blaxploitation soundtrack canon. Many years later I finally found a good-quality copy of it on Harmless Records’s

Pulp Fusion: Revenge Of The Ghetto Grooves; “Theme From Black Belt Jones,” by the way, was never released on a Coffey LP (a 7” single – now grossly overpriced – was released on Warner Records in 1974, whereas Coffey’s albums at the time were released on Sussex), and there was never an official soundtrack release, though a bootleg came out on vinyl in 2000…recorded directly off the VHS. Luichi DeJesus, who the following year would handle the kick-ass vocoder-heavy soundtrack for Pam Grier’s

Friday Foster, did the actual score for

Black Belt Jones; Dennis Coffey only did the theme song and the “love theme” which plays during the ultra-bizarre “mating” sequence that occurs late in the film.

Well, enough about the soundtrack. The movie itself also made a big impact on me. That summer of 1994 was somewhat special to me. I seem to recall spending most of it drinking and watching kung-fu movies with my college friends. Now that’s the life! We watched Black Belt Jones several times; this was also at the time that I was becoming obsessed with the early to mid 1970s. I was born in 1974, the year this film came out, and Thomas Pynchon writes in his novel V something to the effect that many people are destined to become obessed with the era in which they were born. Well, that summer was when it started for me…but then, at the time the entire ‘70s obsession was in full swing. The Beastie Boys of course were at the center of that, with their “Sabotage” video being a faux-‘70s cop show and ‘70s references throughout their albums (including a Dennis Coffey reference in their 1992 B-side “Skills To Pay The Bills”). To this day I’m still fascinated by this era, and what’s funny is that 1994 is now longer ago than the ‘70s were when I first watched the movie – at the time, Black Belt Jones had only been released 20 years before. But man, as hard as it is to believe, 1994 was 28 years ago! WTF!? Now that I think of it, there might be some kid out there now who was born in ’94 and is thus obsessed with the early ‘90s, the poor bastard...

I watched that video untold times, but at some point lost my copy – I seem to recall someone “borrowed” it. It wasn’t until 2010 that I watched the movie again; this was when Black Belt Jones was finally released on DVD, along with two other Jim Kelly films (plus one with Rockne Tarkington, the actor who was originally set to play Williams in Enter The Dragon). Seeing the movie in remastered widescreen was almost like seeing it for the first time, but man I still remembered all the lines, all the story beats. Hey listen, I should talk about the movie and cut out the navel gazing. So look, no one’s going to say Black Belt Jones is a classic. But I love it. And watching it again the other day (still no Blu Ray release, though), it only seems to have gotten better with age. Clouse and company were very right to get rid of the grim and gritty vibe typical of Blaxploitation and go for more of a good-spirited vibe. This is a fun movie, and Kelly carries it well. He sort of plays a less cocky version of his Williams, from Enter The Dragon, but he still has a bunch of smart-ass lines. Who exactly “Black Belt Jones” is, though, is pretty much a mystery; and yes, that’s his damn name. I mean he’s referred to as “Black Belt” for cryin’ out loud. Well anyway, when Black Belt Jones isn’t having white girls jump on a trampoline by the beach or kicking it in his ultramod bachelor pad (which is also on the beach), he seems to do odd jobs for the government. Or at least some agency. When we meet him, he’s busy protecting some dignitary from would-be assassins. Later in the film, though, he acts more in his personal interests than in any government or law enforcement capacity.

An interesting thing about Black Belt Jones is how its template is so similar to just about any Chinese kung-fu movie you could name. I mean it’s literally about the bad guys trying to take over a martial arts school; that’s pretty much the plot for around a billion kung-fu movies. And man what a school this one is – it’s “sensei” is none other than Scatman friggin’ Crothers, playing the least believable karate master in film history. The movie never does make it clear whether Scatman’s “Pop” actually taught Black Belt Jones, but we do learn that the two men have some sort of a student-pupil connection. However, playing the emotional stuff is not Jim Kelly’s forte, so this isn’t much played up on. The convoluted story has it that the Mafia is leaning on black criminal Pinky; they want a particular building in Pinky’s domain, the building with Pop’s karate school, so Pinky and crew start leaning on Pop. Robert Clouse must have taken to actor Malik Carter, who plays Pinky; Carter even gets an “introducing” credit at the start of the movie. Several scenes are given over to Carter so he can chew scenery as the outlandish Pinky, sometimes strutting and rapping about his awesomeness. While Clouse might have seen a future star in Malik Carter, it was not to be; he only acted sporadically after this, his last role being the “night guard” in Stallone’s Cobra (1986). (I discovered this myself before the Internet Movie Database existed; I saw Cobra on cable TV not long after I got the Black Belt Jones video, and just about freaked out when I recognized none other than Pinky himself as a security guard – even though he was only on screen for a few seconds and didn’t have any dialog.)

When Pinky leans a bit

too hard on Pop, things quickly escalate. But even here

Black Belt Jones does not become a violent revenge thriller a la

Coffy. As I say, Jim Kelly’s Black Belt Jones never really seems to give a shit; Pinky’s plot just gives him another opportunity to “be busy lookin’ good.” Actually that’s a Williams line, but it also describes Black Belt Jones. Kelly is very much on form in this picture; he so outmatches his opponents, never tiring even after hordes of them come at him, that it almost approaches the level of a Bruceploitation movie – like Bruce Le, the fake Bruce who starred in the most loathsome Bruceploitation movies of all, where he’d fight like a thousand people and never even break a sweat. At no point does Black Belt Jones seem in trouble, even in a part where Pinky’s men capture him and attempt to beat him to death, with the warning that if Black Belt fights back one of Pop’s students will be killed. I’ve always thought that the action highlight in the film is the one toward the end on the abandoned train; this is an excellently staged sequence, which still retains the goofy comedy overlay of the film (ie the twitching knocked-out thugs, as if Black Belt has given them nerve damage in addition to a sound beating).

The film also has some of the best foley work ever. It’s totally exaggerated; every punch and kick is magnified on the soundtrack. The producers also add a weird “bone crunching” noise at times, which is so overdone it actually can raise your hackles. It gives the impression that Black Belt’s just ruptured someone’s innards. But my favorite sound effect of all in the entire film is when Sydney, Pop’s estranged daughter (played by a

fierce Gloria Hendry),

bitch-slaps Black Belt before their weird mating ritual on the beach. Gloria Hendry delivers lines with aplomb throughout the film, bad-ass lines that she serves up more convincingly than even Kelly does. And they’re wonderfully un-PC, too, like when she calmly tells one of Pinky’s men, “I’ll make you look like a sick faggot.” She’s got a great one before she bitch-slaps Black Belt, too; when Black Belt tells her he “takes” what he wants, Sydney responds, “My cookie would kill you.” You can check this scene out

here – listen to that bitch slap! And this mating sequence deal, scored by Coffey’s “Love Theme From Black Belt Jones,” is a bizarre bit that features Black Belt and Syndey chasing each other around the beach and beating each other up as foreplay. There’s a random bit, in an altogether random scene, where they come across a fat hippie strumming his acoustic guitar along the beach, and the two sadists smash the guitar up; you can see this at the end of the clip I linked to above. Folks, the fat hippie looks so much like

Wayne’s World 2-era Chris Farley that you almost wonder if the dude traveled back in time – he even has the same overdone reactions as Farley when they grab his guitar.

The climax is underwhelming after the fight in the empty train; it’s pretty goofy, too, with a seemingly-endless tide of thugs coming out of the soap bubbles to be knocked out by Black Belt and then escorted into a sanitation truck by Sydney. And yes, soap bubbles; the final fight occurs in a car wash that’s gone haywire. Also here one will spot a cameo by Bob Wall, who played a sadistic henchman in Enter The Dragon; here he plays a geeky Mafia chauffeur. I’m cool with the underwhelming climax, though, as it retains the spirit of the overall film. It’s the dialog that’s key for me; I could quote this movie all day, from the kid’s “She was bad! She was good!” when referring to Sydney’s karate skills to Black Belt’s triumphant, “Let’s go to McDonald’s!” after foiling Pinky. And of course, Black Belt’s “Batman, motherfucker!” Clouse and crew keep the action moving, with a lot of fun sequences, like when Black Belt employs those white trampoline girls on a heist. It’s a little bumpy at the start, though; I mean I don’t watch a movie titled Black Belt Jones and expect to see Scatman Crothers arguing with his heavyset girlfriend. (A scene which regardless features more wonderfully un-PC dialog, ie “I’ll slap the black off you!”) Once Gloria Hendry shows up it’s as if the movie takes on a new drive, and she acquits herself well in the action scenes, really selling her punches and kicks.

I’ve gone on and on about Black Belt Jones but I feel like I really haven’t said much about it. I’ll just leave it that it’s a fun movie, and I bet it was fun as hell to see it on the bigscreen in 1974 – I can just imagine a pack of inner-city kids enthusing over it in some theater on 42nd Street. And the movie did well enough that it warranted a sequel, something I wasn’t aware of until the DVD release in 2010. And speaking of which…

Hot Potato (1975): This movie was so goddamn stupid I scanned through it and didn’t even watch the whole thing; a half-assed movie deserves a half-assed review. Like Black Samurai, this is another one that has a copyright that differs from the release date; Hot Potato is copyright 1975, so far as the opening credits are concerned, but was apparently released in 1976. It’s also a sequel to Black Belt Jones, though you’d never know it. Jim Kelly plays “Jones,” apparently as in “Black Belt Jones,” but he’s never referred to by that name, and no other actors from the previous film are in this one. Indeed, absolutely no mention is made of that previous film. Hot Potato was written by Oscar Williams, who also wrote Black Belt Jones, but he directs this time as well. What a bad decision for the studio; Hot Potato makes Black Belt Jones look like Citizen Kane. It’s messy and chaotic, and I actually felt embarrassed for Jim Kelly. Whereas the previous film had an accent on comedy, it still featured some violent action and everything didn’t seem to be a joke to the characters. Not so here; the entire stupid movie is nothing but comedy, and unfunny comedy, to boot – like Jim Kelly and his colleagues watching a fat man and woman challenge each other to an eating contest, and the gross spectacle just keeps going on and on, complete with gut-churning overdubbed “eating” sounds.

Kelly himself looks bored this time…he looks older than he did just a year before, and also for some reason he’s shaved off his sideburns. There are some parts I kid you not where he looks like ol’ Barry Obama – check out the final fight scene. It’s like Obama with a natural! I’m guessing at this point Jim Kelly must’ve realized his moment in the limelight had already passed him by; surely he had to realize this movie was a turkey. Maybe he did it because he figured the guy who wrote Black Belt Jones couldn’t do him wrong. Obviously he was proven wrong. Or hell, maybe Kelly just wanted a vacation in Thailand (the entire film takes place there – again, a far cry from the urban setting of the previous film). I also feel bad for the Warners marketing department, as they had to try to get people to pay to see this piece of shit. Well, I’ve spent enough time on this one…it’s lame, Jim Kelly’s barely in it (and when he is, he’s usually just standing around), and the focus is on lame comedy throughout. What’s crazy is, despite the suckitude, the film actually looks like a big-budget venture when compared to the cheap productions Kelly would find himself starring in next. Speaking of which…

Black Samurai (1976): As with

Hot Potato, this one has differing copyright and release dates – it’s copyright 1976, but seems to have been released in 1977. It certainly seems more “mid-‘70s” than “disco ‘70s.” Even though it isn’t a big studio production like his previous films, Jim Kelly is back to his old self in this one…you’d think it was actually shot

before Hot Potato. Maybe he thought it would lead to a franchise – which the film should have. Well anyway, this is of course a filmed adaptation of

Marc Olden’s Black Samurai – specifcally, an adaptation of

Black Samurai #6: The Warlock. While lots has been changed to accommodate the small budget (the entire second half of the film takes place in one location, for example, despite the globe-hopping of the source novel), the film is still faithful to the bare bones of the novel’s plot. And almost all of the characters from

The Warlock are here, though in a lessened state: Synne, the hot-as-hell black beauty of the novel, has lost her silver hair; Bone, the hulking gay albino henchman, is a black guy (though it’s intimated in overdubbed dialog during the climactic fight that he’s still gay in the film); and most humorously of all, Rheinhardt, the werewolf in the novel, has been changed to…a midget. But then there

were midgets throughout

The Warlock, and sure, they were

transvestite midgets who wielded whips and wore s&m getups, but at least director Al Adamson was still somewhat faithful to the novel with this change.

But he made some strange changes which were

not faithful to the novel. For one, Robert “Black Samurai” Sand (ie Jim Kelly) does not report to former President William Baron Clarke in the movie; instead, Sand works for D.R.A.G.O.N. (as in, “Enter The;” no doubt Adamson was trying to refer back to Kelly’s most famous movie). And whereas Robert Sand in the novels was a somewhat-terse badass who favored a samurai sword and a .45, the Sand of the movie is a

James Bond wannabe, complete with a

Thunderball-esque jetpack. He also drives a

purple 1972 Dino Ferrari. But man, if Adamson had dispensed with this stuff, he might’ve had sufficient budget to do a more faithful adaptation of the novel. I mean for one thing, Sand uses his samurai sword in the novels, but here he mostly relies on his hands and feet; he shoots one guy with a revolver, and later in the film affixes a silencer to a .45 (for absolutely no reason, as he’s in the friggin’ jungle at the time), but he never fires it. And he only uses a samurai sword briefly in the climax – to cut the ropes off someone. My assumption is Adamson whittled down on the sword action because it would’ve cost more so far as choreography went; it’s much cheaper to have actors just pretend to be kicked in the face than to be chopped by a sword.

But now let me tell you how I personally learned about

Black Samurai, because I’m sure you all are dying to know. I grew up with an obsession for kung-fu movies, and the early ‘90s was a cool time for this because it seemed like a ton of them suddenly came out on VHS. I built up quite a collection, despite not having much money, and on one of the videos I got there was the trailer for

Black Samurai. I no longer recall what kung-fu video in particular it was that featured this trailer, but it would’ve been something I bought in 1994. This trailer, which you can see

here (it was also included in Alamo Drafthouse’s 2012 Blu Ray release

Trailer War), made a big impression on me. At the time I was in college, and we’d often film impromptu kung-fu parodies or whatnot…I recall often mocking this goofy commercial, in particular the line “half the world’s out to kill him.” At the time I had no idea how

Black Samurai itself could even be seen – all I had was the trailer on the video. Then in 2000 or so

Black Samurai was released on VHS and DVD…but I quickly learned that it was edited, with the nudity and violence removed. Fuck that! It was also at this time that I learned of Marc Olden’s source material, and while I eventually got the actual books, I still never sought out Al Adamson’s film. Actually that’s a lie, as I’d read somewhere that in the ‘80s the film had been released uncut on VHS, but this video was impossible to find – at least impossibe for

me to find. And now that I think of it, I’m assuming it was this ‘80s video release that was being advertised on that video I purchased in the early ‘90s.

Well anyway, in one of those random flukes,

Black Samurai was released on Blu Ray the other year as part of “The Al Adamson Collection,” and friends it’s the uncut version that was originally released in grindhouses and drive-ins in 1977. It was a strange experience to actually watch this movie so many years after discovering it via that trailer; I almost found myself getting misty-eyed, but that was probably the cheap blended whiskey I was drinking at the time. And booze (or drugs) would certainly be recommended for anyone who chooses to watch

Black Samurai. But then, the movie isn’t

that bad, even though people often rake it over the coals (just check out Marty McKee’s review at

Crane Shot). I mean yeah, it

is lame, but it isn’t nearly as bad as

Hot Potato. And hell, I’d still rather watch

Black Samurai than

The Eternals. Also, the movie is deserving of at least some respect, as it was the only film adaptation of a men’s adventure series in the ‘70s – the decade that saw a glut of men’s adventure paperbacks, and

Black Samurai was the

only one that made it to the big screen.

I’d love to know what Marc Olden thought of the film. Many years ago his widow Diane told me via email that Olden never met Jim Kelly, “though he admired him.” I was bummed to learn that Olden never got a chance to meet the man who brought his Robert Sand to life. One thing everyone can agree on is that Jim Kelly was the perfect Robert Sand. Unfortunately Al Adamson and his screenwriters didn’t understand the source material, because Kelly, who didn’t have the greatest of range, could’ve easily handled the character as presented in Olden’s novels. Indeed, the Robert Sand of Olden’s novels doesn’t say much – but when he does says something, it’s pretty bad-ass, and then he gets to the ass-kicking. Kelly could’ve handled this. But given how he had all the best lines in Enter The Dragon, the directors of his ensuing films tried to replicate that, so the film version of Robert Sand is a blabbermouth when compared to the novel version. He also lacks the samurai training and mindset; indeed, “Black Samurai” seems to just be this Robert Sand’s codename. He’s basically just a regular movie spy, with all the customary gadgets, only one with a little more focus in karate. No mention is made of him being an actual samurai.

It's been twelve years(!) since I read

The Warlock, but so far as I recall the bones of the novel’s plot are here in the film. And speaking of which, I really enjoyed

The Warlock, but am only now starting to read the series from the beginning…not sure why I took so long, but I think it’s because I was also reading Olden’s

Narc series and just wanted to focus on it first. Well anyway, same as in the source novel, the plot hinges around black magician Janicot, the warlock of the original novel’s title, taking captive Toki, daughter of Sand’s samurai trainer Mr. Konuma. Adamson and team have changed the relationships a bit, but Toki is still Robert Sand’s beloved in this one – however as mentioned Jim Kelly didn’t have the greatest range, thus he never seems all

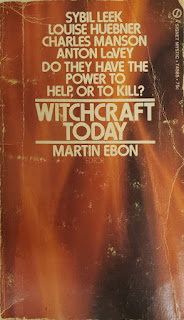

that fired up about rescuing Toki. In fact, Toki’s practically an afterthought. Oh yeah, I recall Janicot ran a sideline operation in the novel where he filmed various noteables in his black magic sex orgies, using that for blackmail…none of this is in the film. Janicot has practically been neutered in the film version; Bill Roy’s portrayal of the character is more Paul Lynde than Anton LaVey. (Seriously, it would be easy to imagine this Janicot as one of Uncle Arthur’s “special male friends.”) He makes for a lame duck villain, and his “warlock” nature isn’t nearly as exploited as in the novel.

But let’s talk about the boobs! Seriously though, this uncut version of Black Samurai has been lost for many, many years, but the topless gals are here in all their glory. Adamson strings nudity throughout the film, befitting a movie intended for grindhouse theaters; in particular we have a dazed-looking blonde who does a practically endless striptease halfway through the film, topless throughout (the camera cuts away for the big finale when she pulls off her panties, however). Marilyn Joi as Synne also gets her top torn off by Chavez, Latino thug who in the novel ran his own drug empire, but here in the novel is another of Janicot’s men. Actually he comes off as more threatening than Janicot himself. Oh but randomly enough…Adamson kept the “lion-men” in the movie! One of the more outrageous elements of an outrageous novel made it to the film; randomly enough, Sand at one point is attacked by a pair of black guys dressed up like the savages in a 1930s jungle movie. One of them he seems to relish in killing; I’m not sure if the bloody violence was cut from the previously-available versions, but here in this Blu Ray Sand makes a few bloody kills. For example he tosses a boulder on one of the lion men, and we get a closeup of the spouting blood as the lion man floats in water.

The karate scenes are actually pretty good. Once again Kelly comes off as vastly outmatching his opponents, but there seems to have been an attempt at actually making him work for it at times. For example the fight with Bone (Charles Grant) is pretty good – livened up by some postproduction dubbing where the two trash-talk each other. Here Sand calls Bone all kinds of inappropriate-for-today gay slurs, adding to the over-the-top vibe of the film; making it even more crazy, the actors clearly aren’t saying anything to each other and all their dialog has been dubbed in after the fact…and since you hear their voices but their lips aren’t moving it gives it all a surreal, dreamlike quality. Unintentionally avant-garde, I guess. Also, Jim Kelly fights a friggin’ vulture, but it’s staged so ineptly that again you wonder why Adamson didn’t use the money for something else. And the fight with Janicot is so lame you wonder why they even included it. But Kelly really seems invested in the role, even if the production is meager compared to his previous movies – I mean we’re talking “boom mic audio.”

Speaking of cost-cutting, Adamson saved on the soundtrack, too.

Black Samurai does not feature an original score. Adamson instead uses what’s now known as “sound library” music, ie production music created by various labels for use in film, TV, radio, and etc. The “theme song,” for example, is actually “

Flashback” by Alan Hawkshaw and Keith Mansfield. The song that plays throughout the endless stripdance sequence is “

Soul Slap” by Madeline Bell and Alan Parker. Some years ago a blogger by the handle Fraykers Revenge created the soundtrack for

Black Samurai, tracking down each song from his vast collection of sound library releases; unfortunately his blog is long gone, but perhaps the soundtrack is still available somewhere on the internet.

I’ve been going on and on, but I’ve gotta say Black Samurai isn’t terrible. I mean Hot Potato is terrible. Black Samurai is actually watchable, and it’s at least good enough that you wish it was better – that it had more money for the setups and locations. Jim Kelly acquits himself well, proving he could carry a film…even when wearing a very un-Robert Sand tracksuit. There’s definitely a camp quality to it, which always helps. But then perhaps my positive sentiments are due to the uncut Blu Ray; I might be complaining just like every other reviewer if I was talking about the cut version that was previously available on the market. At any rate, it makes one sorry that there wasn’t a followup; the following year Kelly starred in another Adamson production, Death Dimension, and you kind of wish they’d just done Black Samurai II instead.

Well friends, I was going to review more of Jim Kelly’s movies (he’s always been one of my favorite actors…I mean he’s the only guy in film history who could be in a movie with Bruce Lee and actually come off as cooler than Bruce Lee), but as usual I ran on so long that I’ll have to get to the others anon; Three The Hard Way, Death Dimension, Golden Needles, etc.