Trawling the depths of forgotten fiction, films, and beyond, with yer pal, Joe Kenney

Thursday, May 28, 2015

Mafia: Operation Cocaine

Mafia: Operation Cocaine, by Don Romano

March, 1974 Pyramid Books

The second entry in the Mafia: Operation “series” is courtesy the same authors who delivered the stellar first volume, Operation Porno: Robert Turner and Allan Nixon. These guys make for one hell of a powerhouse combo, for again they have turned out an uber-sleazy tale of the underworld and the fucked-up criminals who populate it.

In a way Operation Cocaine is like an installment of Marc Olden’s Narc series, only without a hero; they’re all villains in this story. But it retains the same Byzantine plotting as one of Olden’s books, with every character scheming against the other to get a piece of the cocaine empire. That’s true for the first half, at least, after which the novel almost turns into a sort of Sharpshooter or Marksman variant, with a psychotic lone wolf swearing vengeance against the Mafia…and really busting the shit out of them.

But for the first half the novel’s a bit structureless, and is comprised of a barrage of characters with similar names plotting against one another. This detracts a little from the eventual sleaze impact, which when it occurs is almost but not quite on the level of Operation Porno. Also unlike that previous book, there’s really not much about the cocaine business in this one; it’s more of a revenge scenario, as the ruler of a South American cocaine empire is set up by the Mafia and swears revenge.

This character is the closest we get to a hero, or even a protagonist: Paul Duray, Belgian-born 45 year-old who lives in ultra wealth and has a lucrative deal with the New York-based branch of the Mafia, which spend lots of money on his top-quality cocaine. The novel opens with sabotage, as the dude who unwittingly carries the shipments of coke up to New York is killed (while thinking about the awesome blowjobs he gets from a New York whore, naturally – I’m telling you, these authors are masters of sleaze). This sets off a chain of events which will, just like in the previous book, end on almost Shakespearian levels of tragedy.

New York Mafia bos Carlos Carriglio, head of the Prescipio Family, vows to find out who stole these three kilos. He has Duray himself investigated, as it appeared to be an inside job, even though Duray is so wealthy, not to mention that it wouldn’t make any sense for him to rob from his own stash. Nonetheless Carriglio tasks his top caporegime, Al Dennono, with looking into Duray and perhaps making him and/or his associates sweat a little, in particular Duray’s top assistant, Flip Hondo. It’s Hondo’s death that sets Duray off and turns him into an ostensible Johnny Rock.

Before that happens though we get a bit too much about Al Dennono and his screwed-up world. Hiding his “lavender” proclivities from his boss, Dennono is gay and is currently smitten with a young male hooker named Nino DeSico who has silicone tits and sometimes, we later learn, puts special silicone attachments around his shaved privates so his male customers can screw him like a girl…! Nino’s got a stupid brother named Baba, whom Dennono is training as an underling, despite the guy’s stupidty – all so Dennono can keep getting special favors from Nino.

This stuff gets a lot of print; there’s even an arbitrary part early in the book where Paul Duray, looking for quick cover, finds himself in a gay bar in Manhattan, and we get lots of description of this lifestyle. But the authors don’t shirk on the straight sex; this comes in the form of Lacey Johnson, a smokin’-hot redheaded “actress” who in pure ‘70s style wears a silver coke spoon as a necklace, so that it dangles in her “impressive cleavage.” Flip Hondo hooks up his boss Duray with her, warning the older man first off that the gal is a fiend for coke, totally addicted to it.

Paul could care less, and takes her back to his swinging bachelor penthouse on Park Avenue. Here we get an explicit sequence that brings to mind the shenanigans in Operation Porno, as first Paul screws Lacey, who we learn cannot achieve orgasm, “regular” style…and then afterwards he covers her nether regions with cocaine, puts some on his own privates, and then they go at it big time! Harold Robbins couldn’t have written a more over-the-top scene. Not only does Lacey achieve that ever-elusive orgasm, but she also feels like she’s falling in love with Paul Duray, and he’s starting to feel the same for her.

But when Flip Hondo is captured by Dennono’s goons and killed, Paul goes into vengeance mode. Here the novel kicks into gear as he makes short but grisly work of the various flunkies who are part of Carlos Carriglio’s operation. Paul retains two henchmen/bodyguards, hulking “Peruvian Indians” named Tala and Jorge, and the three make for a very impressive team. First they take out “the Scorpion,” a ‘Nam-trained assassin who was responsible for Hondo’s death, paralyzing him with a curare-tipped dart (shades of The Penetrator) and then hurling his car into the bottom of a quarry.

Meanwhile Al Dennono’s storyline continues to get more and more fucked up. For we learn that Nino, Al’s little transvestite playmate, is in a sexual relationship…with his own brother!! You see, I told you these authors know their sleaze! But yeah, Nino and Baba enjoy going at it, and we get a lot of crazed and wild stuff with the two of them, and then it gets even more crazed and wild when Dennono shows up at Nino’s place unannounced and catches the brothers in the act. When Paul and his two henchmen show up and carry off a numb Dennono, there’s a pair of twitching corpses on the bed, something which a puritanical Carlos Carriglio is desperate to keep out of the papers.

Paul Duray could give Johnny Rock and Philip Magellan a class in sadism: his offing of Dennono is particularly novel. They take him to one of Carriglio’s legal operations, a laundromat, and stuff him into a dryer, Paul confident that Dennono will be knocked out of his shock by the heat and the centrifugal force of the dryer, and thus will be cognizant of the horrifying way in which he’s dying. And as the man pleads and bangs against the dryer door, Paul knows he was right. Next up Paul and the henchmen (who he raised as sons) take on a six-man task force Carriglio sends after them.

In a move Rambo would later endorse, the three take positions on the rooftop of a building across from Paul’s apartment building and launch flaming arrows down at the two cars that wait in ambush outside it. The authors are also masters of dark comedy, and this sequence features an almost proto-Simpsons gag, as some random dude in the apartment building happens to be watching a gangster movie on television while the battle rages outside, and when he gets up to turn the channel he’s hit in the head by a stray bullet.

Along the way Paul has learned that the culprit behind the kilo hijack was a guy named Errico Rosario, one of Carriglio's Mafia men and a person Paul had been training to be his second in command. Rosario’s plan was to sow dissent against Paul so that Carriglio would have him killed, and then Rosario would become the owner of Paul’s cocaine empire in South America. As if that wasn’t enough, Rosario has also moved in on Lacey, who figures she’s been dumped by Paul – she feels that her lot in life is to be used by men and then dropped. So she plays right into Rosario’s hands, especially when he offers her some coke.

Using Lacey as bait (and the little nympho, we learn, has introduced him to Paul’s little coke-on-your-privates trick), Rosario hopes to roust Paul out of hiding. But as usual Paul Duray is two steps ahead and captures both of them. Another sadistic death ensues, as Paul takes his captives out on his cruising yacht, strips Rosario down to trunks, and ties him to a line, tossing him into the water behind the boat. This all works up to a gory send-off for Rosario, who is chopped to hamburger by the powerful propellors.

Lacey suffers an equally crazed fate. Paul, feeling betrayed by the girl, leaves her to sulk in her prison of a room as he takes the yacht on down south, announcing he’s due a “vacation” after all this nastiness in New York. Finally he talks to Lacey, playing nice, and offers her a drink. Only, he’s dosed it with a mixture of cantharides (ie Spanish Fly) and strychnine. This leads to a mega-horny and nude Lacey screaming on the deck of the yacht, pleading with Paul, Tala, or Jorge to have sex with her – even threatening to kill them if they don’t. The cantharides, we’re informed, were used by the Peruvian Indians as punishment for unfaithful wives.

Strangely, the authors don’t exploit Lacey’s eventual rape, as Paul figures at length that she’s “had enough” and then he and his two henchmen take their turns with her in a fade to black scene. But when they dock at a Florida port a few days later while a sort of pirate celebration is going on, they find that Lacey is dead, killed by the fatal cantharides poisoning. This isn’t something Paul intended to happen, but he’s as resourceful as ever, disguising the girl’s body as a mauled pirate victim and dumping it into the water along with the other effigies – part of the bizarre annual celebration, we’re told.

The reader will of course understand the novel is headed for a dark conclusion, and here in the home stretch they dole out the final betrayal. Jorge and Tala, who as mentioned were raised from childhood by Paul, have been given an offer by Carlos Carriglio: get rid of Paul Duray and his cocaine empire will be theirs. This is a savage scene, as the authors cut straight to a nude Paul Duray, cast naked and adrift in the middle of the ocean, with no hope of rescue or of swimming to safety; we’re informed in one of the most abrupt but disturbing finales ever that he’s nothing more than a mauled corpse a mere three hours later.

While taking a bit too long to get going, Mafia: Operation Cocaine is nevertheless a masterful blast of lurid pulp, which makes it a shame that the authors’s next installment, Operation Hitman, was their last for the series.

Monday, May 25, 2015

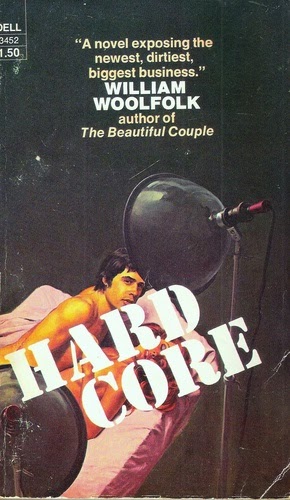

Hard Core

Hard Core, by William Woolfolk

January, 1974 Dell Books

William Woolfolk was an author in the Burt Hirschfeld mold, and had his biggest hit with a novel titled The Beautiful Couple, a roman a clef about Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. I haven’t read that one, but if the paperback-only Hard Core is any judge, Woolfolk is more in the “literary author” realm than you’d expect for someone in the trash fiction genre.

“Pornography hits home tv” goes the back cover, but the reader looking for salacious thrills must be warned that Hard Core is more about the business end than the sleaze. Also of interest is that the back copy mentions videotape as being the new source for porn, but the technology in the actual text is “vidtapes,” which we’re informed are “4x5 photographic card”-sized things that you insert into the “vidcassette attachment” of your TV. They’re created from a holograph technology that retains perfect picture quality and color preservation. In other words, they’re absolutely nothing like actual videotape!

But this new technology has previously been used for industrial films and whatnot, and hasn’t been a big hit with the public. But that was before they started making porn vidtapes, baby! Now it’s becoming a million-dollar industry, and the novel is interesting in how it predicts the porn boom of recent decades. However our hero, a 27 year-old reporter named Paul Gersbach, is unaware of this growing cult trend, and when he does become aware he doesn’t decide to research the industry out of professional interest, but more for revenge, in what amounts to a very lame setup.

But Paul himself is a lame protagonist. One of the biggest problems with the novel, Paul is neither too goody-goody nor too depraved to be of much interest; what the novel really needed was a Harold Robbins-style protagonist. This is the same thing I complained about in my review of Norman Spinrad’s somewhat-similar (but much better) novel Passing Through The Flame. No, Paul is a sort of starch-collared square who goes through the novel judging everyone, ultimately building ill-will in the reader. I think the novel would’ve been better off without him.

Paul comes into the world of porn via unusual means: through the suicide of his soon-to-be mother-in-law. Leaving New York, where he has a job at a pretentious newspaper, Paul travels to Sweetzer, Ohio, to be with his naïve, virginal fiance Jennifer Naylor. Jennifer’s mother Helen is a professor at the local university, and all the academic snobs congregate at a party at her home the night Paul arrives. But something seems up with Helen Naylor, and next morning – after Paul has taken Jennifer’s virginity in a scene that goes more for poetry than sleaze – they find her dead in her bed. Later Paul will be informed she killed herself with strychnine.

Our reporter hero does his legwork and finds out that Helen was being blackmailed. Some idiot left her a threatening note about something he saw her in, and the idiot was dumb enough to leave his name on the note. Paul goes to the address, to find a shut-in freak who has stacks of boxes marked Confidential Cassettes. The freak gamely pops in the vidtape he wrote to Mrs. Naylor about, and it’s a sort of surveillance camera-style footage of women engaged in lesbian shenanigans. Helen Naylor is one of the participants; the shut-in has to point her out to Paul, who has watched the entire thing in sickened shock.

Rather than punch out the blackmailing shut-in who, you know, inadvertently caused the suicide of Helen, Paul instead vows vengeance against…Confidential Cassettes. I guess this is because his assumption is they’ve illegally filmed a “lesbian hangout” and released it, hence the surveillance footage aspect of the tape, but still. How much more interesting the novel would’ve been if Paul had just decided to research the company without the albatross of a vengeance subplot – a subplot which basically disappears.

Paul’s snobbish newspaper isn’t interested in the story; he’s recommended to take it to the more sensationalistic domain of William Graham Pritchett, an old newspaper magnate who’s so “William Randolph Hearst/Charles Foster Kane” that he even has his own Xanadu. The editor at one of Pritchett’s papers is interested in the story, and suggests that Paul even get a job at Confidential, so he can make double the buck – paid as an employee of Confidential Cassettes, and also paid for the series of article he’s secretly writing.

Confidential is set up like the old Hollywood studio system. It’s owned by yet another megamillionaire: Evan Hendershot, an epicurian with bisexual tendencies, but it’s run by a former football player named Tom Fallon, who serves as production chief. Fallon is gay for Hendershot, who merely toys with the man’s feelings, instead preferring to occasionally sleep with Confidential’s top star, brunette babe Sheila Tomkins. There’s also Max Rand, who acts as president, and a former adult paperback hack named Ed Ciranni who serves as the main writer for the company.

Paul’s able to bluff his way into a writing job, and they hook him up with Ed. The two come up with a series of films titled “The History of Pornography,” focusing on salacious moments from ancient literature. One problem with Hard Core is that the employees of Confidential Cassettes come off as a little too literary; each of them capable of sitting around and discussing Balzac or esoteric realms of ancient Roman literature. It’s a bit hard to buy, and comes off more as if Paul’s still hanging around with the snobbish academics back in Ohio.

The director who will handle the History is an old Hollywood pro named Frank Murdoch, who himself comes off like a poor man’s Orson Welles. The director of Very Important films in the ‘40s that made no money, he’s now a shadow of his former self, and will do any work for a buck. He’s also a drunk and doesn’t want to talk about the past with Paul, who is a major fan of Murdoch’s work and can’t believe the guy is sullying himself in the world of porn.

The first episode of the History will focus on Phryne, the most famous courtesan of Ancient Greece, so a massive hunt goes on for the star. Evan Hendershot insists on Sheila Tomkins, who has been dubbed “the Queen of the vidcassettes,” as she has starred in so many of them and is the closest the industry has to a true star. One thing Woolfolk curiously leaves unstated is if Sheila actually has sex in her movies. Believe it or not, this little detail is never mentioned…but then, Woolfolk hardly ever bothers describing the actual movies that are filmed.

It’s true…only once or twice do we actually get to read about one of these Confidential Cassette releases, and in both cases they’re those “ secret surveillance camera”-type deals. The episodes of the History that we read about usually just feature nudity, like Sheila as Phryne disrobing before an audience, or a later film based on Bluebeard’s eight wives where she plays each of the wives, killed again and again – but sex is never mentioned. I started to wonder if by “porno” Woolfolk meant the early ‘70s Hollywood idea of it, ie lots of nudity but no actual onscreen sex, but then later he’d mention the hardcore shenanigans of those surveillance-type movies, so I was just plain confused.

Paul gets one gander at Sheila and goes head over heels. Another interesting tidbit about Woolfolk: he doesn’t really describe (and certainly doesn’t exploit) his female characters at all. We just learn that Sheila has dark hair and eyes and is very, very sexy. Rarely does Woolfolk describe anything else, other than the high fashion clothing she might wear. So as you can guess, when it comes to the very few sex scenes Woolfolk is indeed one of those authors who goes for the poetical approach, comparing climaxes to cresting waves and whatnot; again, more Burt Hirschfeld, less Irving A. Greenfield.

He might be bland, judgmental, and sort of forgettable, but Paul Gersbach is basically a cad; after taking young Jennifer’s virginity, he’s basically left her there in Ohio, telling her he has a story to finish back in NYC. Promptly be begins banging the hot chick who lives down the hall from his furnished apartment (again, zero details per the Woolfolk norm), and now he’s in lust with a “porno star.” Every once in a while Woolfolk will bring Jennifer back into the tale, and you feel bad for her, as she’s all alone now, her mother dead and all, her fiance Paul away in New York, and no one to be with her back in smalltown Ohio.

We get a lot of detail about the business of making adult vidcassettes. There’s a bit of a trash fiction vibe with the introduction of Evan Hendershot, who himself gest a case of the lusts – for Paul. Now Evan, who has a casual sex thing going with Sheila (she’s the only woman he’ll have sex with), tasks his favorite actress with wooing Paul, so Evan can swoop in and draft him on over to the world of the gays. Meanwhile Paul himself oblivously goes about the business of writing scripts for Confidential Cassettes, learning that his coworkers are all nuts.

Former Hollywood great Frank Murdoch gets the most print. Now a drunk, he falls further and further down the spiral, constantly butting heads with Tom Fallon, who treats Murdoch like dirt. Then Murdoch, who tells Paul that the world of porn is the world of no return, drinks himself to death, after which Fallon himself runs afoul of some mobsters and is beaten to a pulp before getting run over by a car. Likely realizing that an industry in which two colleagues die in the span of a week or two is not a safe industry to be in, Paul runs back to Ohio.

Again, it’s all about the business, less about the sleaze; Paul finds himself courted by both Confidential Cassettes and Hearst-esque Pritchett, who himself is looking to get into the adult vidcassette market. Both want Paul to be their head of production. Paul, his collar really starched at this point, says no – Frank Murdoch’s parting words have affected him. He goes about the business of planning to marry Jennifer, but he still lusts after Sheila. But when his articles for the Pritchett papers are scrapped and wily Max Rand screws over Paul’s chances of getting a teaching job at that Ohio college, back he goes to New York.

The Paul/Sheila deal plays out very strangely…sick of getting blue-balled, Paul takes advantage of her one night after she’s taken a valium! Here we get the most detailed (but still poetic) sex scene in the book, as Paul rapes the unconscious girl. Good grief! Now he’s really in love…but another curious tidbit is that, even though he and Sheila apparently begin dating, Woolfolk doesn’t bother telling us about it! We only learn in passing mention that Paul has been “spoiled” by sex with Sheila, who apparently treats him to some good and proper bangings. Oh, and Jennifer leaves him for someone else.

Hard Core proceeds to get more twisted as it nears its conclusion. More death and ruin in the world of porn, as the gay community gets upset over some new Confidential Cassettes release, protests outside their building, and then one of the protesters knifes Sheila to death as she gets out of her taxi! This leads to one of the sicker moments in the novel, as a beaming Evan Hendershot proudly unveils to Paul the latest Confidential Cassettes release – the videotaped autopsy of Sheila Tomkins!

The ending is total ‘70s downer, with Paul so shellshocked and benumbed, so corrupted by the world of porn, that he ends up turning away from everything and giving himself to that depraved, lecherous fop, Evan Hendershot, who despite it all has in fact won the bet he made with Sheila. Paul has now become the man’s new Tom Fallon, a sexual playmate he can use and abuse, who regardless will run Confidential Cassettes with a perfect understanding of how the porn business works.

Neither very good nor very bad, Hard Core instead comes off as forgettable, stuck with a frustrating protagonist, a lack of lurid thrills, and too little detail about the actual product Confidential Cassettes turns out. Reading this book, you get the feeling that William Woolfolk had never even seen a porn movie, but didn’t let that stop him from writing about them.

Thursday, May 21, 2015

War Of The Worlds: The Resurrection

War Of The Worlds: The Resurrection, by J.M. Dillard

September, 1988 Pocket Books

Mostly forgotten today, War Of The Worlds was a syndicated TV show that ran for two seasons, starting in the fall of 1988. I watched the first season at the time and loved it, though I didn’t know anyone else in my high school who watched it (even the sci-fi geeks didn’t). In years to come I usually found that I was still the only person among my various groups of friends who had even heard of it.

Flash forward all these years later and War Of The Worlds (sometimes subtitled “The Resurrection”) is still obscure and has not garnered much of a cult following, or at least one that I could find on the interweb. The complete series has been released on DVD, though, and last year I picked it up, but so far have only watched the first few episodes. The show was clearly low budget, filmed in Canada, and had a definite campy/dark comedy vibe, coupled with some still-unsettling gore effects, and to tell the truth it was all pretty entertaining.

Picking up from the 1953 George Pal film (not the HG Wells novel nor the Orson Welles radio production), the TV series veered more into horror than sci-fi, with the aliens (not Martians, but revealed to be from some planet called Mor-Tax) now cast as creepy monsters in the vein of Robert Heinlein’s The Puppet Masters. Able to pull their slimy, “apelike” bodies into humans, they now walked around in host bodies and waged an undercover war against mankind. The show traded more on suspense and horror than the big-budget action of the George Pal film, with the canvas much more reigned in than the global chaos of the movie.

The series kicked off with a two-hour pilot film, which served as the basis for this novelization courtesy J.M. Dillard, an author mostly known for her Star Trek novels. Dillard’s book achieves the ultimate goal of a novelization: it reads like its own work, and not just a synopsis/rehash of a TV episode. Also of note is that Dillard’s book, while very faithful to the pilot episode, features elements and incidents that didn’t make it to the final cut, and likely weren’t even filmed. In one particular case an entire character exists in Dillard’s book that was absent from the show: Dr. Clayton Forrester, the hero of the ’53 film who in Dillard’s novel is a supporting character.

Rather, the main protagonist of the novel (and the series) is Dr. Harrison Blackwood, a 40 year-old scientist who was raised by Clayton Forrester, Harrison’s parents being killed by the aliens during the ’53 invasion. Clayton Forrester raised the boy as his own, and these days Harrison is a top astrophysicist at the Pacific Institute of Technology; he’s also a government-hating left-winger who has vowed to continue the research his foster father started after the aborted alien invasion. He’s also one of those types who rides a bicycle to work and constantly “munches” on granola bars.

As for Clayton himself, he’s long retired, and in ill health with a plumb heart. He’s barely in the narrative at all – and a good thing, too, as every time I read “Dr. Clayton Forrester” I kept picturing Trace Beaulieu’s character from Mystery Science Theater 3000. My assumption is the producers were uncertain if they would really have Clayton in the pilot episode, as the character is so incidental to the plot, and so seldom featured, that you can see how he’d easily be removed without affecting anything. And for that matter, when Clayton does show up it’s in very superfluous scenes.

One of the hardest elements to buy about the show was that no one in the then-current world of 1988 remembered the alien invasion of 1953. Dillard tries her best to make this palatable by calling it a “mass denial” the human race has adopted when dealing with the events of ’53, with most people having successfully pushed it out of their minds. Those who lived through it refuse to think of it, and those born after it have only learned the bare minimum about it. There’s a vaguely-explored conspiracy angle that the government has been behind this mass denial, mostly so as to stave off any potential panic – the aliens were killed by Earth bacteria in 1953, and that’s that.

Only, Clayton Forrester knew this view was shortsighted, that the aliens very likely could return, and raised his adopted son to believe it as well. Hence Harrison retains Clayton’s distrust of the government and the military, and also shares his obsession with researching the aliens, despite the mass disbelief in them. Harrison’s sole associate is Dr. Norton Drake, a black parapalegic who specializes in studying radio waves and whatnot. As we meet them they’ve brought in a new associate: Dr. Suzanne McCullough, hotstuff brunette who has come here to California from Ohio along with her young daughter, Deb.

Suzanne is a microbiologist and has no idea what job she’s even been offered here at the “PITS.” This leads to instant chemistry/dislike between her and Harrison, something which per TV tradition went on throughout the series. At great length Suzanne learns that Harrison wants her to analyze various alien DNA from ’53, including even a corpse he’s managed to get hold of (another of those scenes not in the actual pilot film). Suzanne was a toddler when the aliens invaded and only has bare memories of it, unlike Harrison and Norton, who himself lost family in the attack. In the novel, we also learn that Suzanne is “second cousins” with Suzanne Van Buren, the woman Clayton Forrester was going to marry, before she went insane after the ’53 invasion.

But like everyone else Suzanne refuses to think much about the aliens, and it’s only after much struggle that Harrison wins her over. This is mostly done through the first of the novel’s few action scenes, as a group of hippie-style terrorists, the People’s Liberation Army, attack a remote army base in Jericho Valley, Arizona. The place holds radioactive waste, and the terrorists want to use it for their nefarious goals. Dillard spends a goodly portion of the early quarter in the perspective of Lena Urick, the sole female member of the terrorists.

What the terrorists don’t know is that Jericho Valley is one of the places where the army stockpiled the alien “corpses” from ’53 – aliens that weren’t really dead, but in stasis. What they also don’t know is that the leaking radiation at Jericho Valley has gradually destroyed the bacteria in the aliens’s system, so that now they have come back to life – right after, coincidentally enough, the terrorists have blown away the few soldiers manning the base. Now comes the icky stuff from the pilot, as the few awake aliens take on the corpses of the terrorists as host bodies – this leads to lots of dark humor in the novel (and especially the pilot film), as they’re basically decomposing corpses walking around.

Dillard spends a lot of the narrative in the perspective of the aliens, all of it written in ugly-looking italics. (Also, in true cheesy sci-fi standards, all of the aliens have names that begin with “X.”) Interesting too that here, even with the aliens, Dillard writes from the perspective of a female: Xana, a member of the “Advocacy,” ie the trio who rule this particular grouping of aliens. Throughout the novel Dillard writes mostly from the perspectives of either Suzanne or Xana, which gives the novel an almost feminine tone – strange, when compared to the “boy’s world” tone of the actual pilot and series.

Anyway, the awoken Advocacy beams a message to home planet Mor-Tax, off in the Taurus constellation, and this alerts Norton’s computer back at PIT. Harrison breaks off a date with his ultra-annoying fiance, Charlotte (a character promptly removed from the series after this pilot film – even the producers must’ve realized how annoying she was), and drafts Suzanne for a several-hours drive to Jericho Valley. There they find the army has moved in, inspecting the destruction; leading them is Lt. Col. Paul Ironhorse, Delta Force badass (played most memorably by Richard Chaves in the series – a guy most known for playing Poncho in Predator).

Harrison immediately realizes that the worst has happened: several aliens have reawoken and have stolen away with the few hundred other barrels stored at Jericho Valley, each of which contains a comatose alien. However, this leads to more stonewalling and disbelief, as the army insists it was just the terrorists who took off with the radiation. Most of The Resurrection is given over to Harrison proving his case to both his colleagues and the government, and you start to wish it would just get to the fireworks. But there’s no more action until much later, when Harrison again tracks the aliens down to a farmhouse in the countryside.

Ironhorse is here, once again, about to lead his Delta squad on an assault against the place. The ensuing action scene is a lot bigger in the pilot episode than in the novel, but it has the same outcome: all of Ironhorse’s men are killed, and the aliens again escape. Here though the heroes finally learn how the aliens can take on host bodies, including the gross-out factor that their host bodies melt when killed – as Ironhorse puts it, “like something out of a grade-B horror flick.” This was one of the crazier elements of the series, and always fun to watch, as the aliens would dissolve into puddles of gray goo.

We move into the homestretch as Harrison and team are set up on a secret ranch by the government (the mover and shaker behind the arrangement being Suzanne’s uncle, military bigwig General Wilson) to wage a secret war against the aliens. Why doesn’t the army just go after them? Because if people found out the aliens were still alive, it would cause mass panic! (And more importantly, because that would cost a lot more to film.) They’re even given a (single) military representative: none other than Paul Ironhorse, who by the way enjoys cultivating his “Indian mystique.”

Norton breaks the alien code and learns that they are heading for Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada. Harrison belatedly remembers something special about that base – it’s where Hangar 15 resides (Hanger 18, he says, is disinformation spread by the military; Hangar 15 is legit). This is where the government stockpiled three of the alien spaceships from ’53. If the aliens were to get hold of those ships, there would be no stopping them. But again, instead of calling in the cavalry our heroes must resort to subterfuge, Ironhorse posing as Delta Force instructor making an unplanned, unscheduled visit to the base for cross-training purposes.

Dillard well captures Harrison’s state of fear as he looks upon the alien aircraft, flashing back to his childhood memory of watching his parents blasted apart by one of them. This is something else the pilot episode was unable to capture. But then, something the pilot did better was the ensuing firefight between our heroes and the aliens, who of course arrive at Hangar 15 at the same time, having gotten onto the base due to their Delta Force host bodies. But Harrison et al are able to escape even as the aliens get in their ships – ships which Ironhorse has hidden explosives inside.

This was the only part of the pilot episode that used footage from the ’53 film, as the ships came out of the barn and exploded; I don’t think the show ever again used any of the footage, or ever showed the alien ships again. As mentioned, it was a very low budget affair. The finale of the pilot however was a precursor of practically every episode to follow, with Harrison and team tracing the surviving aliens somewhere, going undercover to roust them, and then turning them into bubbling puddles of goo before the end credits rolled.

Another thing missing from Dillard’s fine novelization is the campy and dark humor of the show, but then it seems that this became more evident in the later episodes. Also worth noting is that the complex alien subplot Dillard works into the novel is rendered moot by the actual show; Dillard has lots of scheming and plotting among the aliens, which in truth I think the show was better without. But then, all this scheming was rendered moot by the second season, which saw a complete overhaul of the series, with Ironhorse and Norton written out and the Mor-Tax aliens replaced by more humanoid foes.

Anyway, I enjoyed Dillard’s book, though in truth I would say it’s only worth seeking out if you are a big fan of the series and want to read an author’s take on the thoughts and feelings of the various characters. But as is the case with most novelizations, you’d be better off just watching the actual show.

Monday, May 18, 2015

The Penetrator #24: Cryogenic Nightmare

The Penetrator #24: Cryogenic Nightmare, by Lionel Derrick

February, 1978 Pinnacle Books

Chet Cunningham redeems himself with this installment of the Penetrator, which is the best one Cunningham’s turned in for a long time. That’s not to say that Cryogenic Nightmare is as masterfully lurid as Cunningham’s #4: Hijacking Manhattan or #12: Bloody Boston, but it sure as hell isn’t as sleep-inducing as #22: High Disaster, which I rank as one of the worst men’s adventure novels I’ve ever read (even worse than Tracker!). But you can’t really blame Cunningham, because like series co-writer Mark Roberts he had to churn out these manuscripts one after another, year in, year out, which is a lot to expect from a guy.

Whatever the reason, Cunningham apparently got his wind back for this volume, which features perhaps the most lurid threat yet – gorgeous women are being cryogenically frozen and sold to the highest bidder! And the man behind it is straight out of the ‘70s: an ultra-styling super pimp who looks like Black Moses-era Isaac Hayes and calls himself Preacher Mann. Unfortunately Cunningham takes his time getting to this cryogenic stuff, with it only given passing mention in the first hundred pages of the 180-page book. Rather, the focus is on Mark “The Penetrator” Hardin going down to West Palm Beach to research Preacher Mann.

Our villain calls himself thusly not because he’s an actual preacher, but because he was known for “preaching” about the benefits of being a vegetarian to his cronies in Harlem, back before his global crime empire got off the ground. Now Preacher Mann operates somewhere out of Florida – Hardin isn’t certain if it’s West Palm Beach or Miami – and he’s so nefarious but so insidious that there’s zero evidence on the guy. Also, despite that we’ve never heard of him before, we are informed that Hardin and Professor Haskins, his mentor back at the Stronghold, have been researching Preacher Mann for the past two years.

Speaking of Cunningham’s earlier work, this one features a callback to his very first installment for the series, #2: Blood On The Strip. Hardin flies his private plane into West Palm Beach and talks to a vaguely familiar mechanic with “sandy” hair and lots of freckles. Hardin knows he’s seen this kid before, and the way the kid’s looking at him Hardin also knows he’s been made as the Penetrator. Sure enough, as he’s driving away from the airport in his rental car, he’s attacked by thugs in a car. Hardin crashes into a swamp, his car exploding due to the arsenal hidden in it, but he secretly escapes, hoping his pursuers figure him for dead.

Only then does Hardin flash back on who the sandy-haired kid was – one of the low-level employees of The Fraulein in Blood On The Strip. Hardin had a few run-ins with the kid in that volume, even slapping him around at some point, and now the kid has sworn revenge. In the years since (interestingly, it appears that real time has passed within the world of the series; meaning Blood On The Strip really took place over four years before Cryogenic Nightmare), the kid has hired himself out to various crime outfits, to act as a lookout for the elusive Penetrator, being that he’s one of the few people to have ever seen him and lived.

Hardin knows Preacher Mann’s up to something big but he doesn’t know what exactly it is. So the first half of Cryogenic Nightmare is mostly made up of the Penetrator going around West Palm Beach and tracking clues. This entails a few brief action scenes like when he crashes a Preacher-owned building and gets shot by a night security guard; luckily, Hardin is wearing a sweater made of “Resistweve” at the time. We’re informed that this material looks like a regular sweater but has bulletproof qualities. Hardin can’t believe there’s such a thing, obviously having forgotten all about the bullet-proof business suit he had made in #15: The Quebec Connection.

A later action scene has Hardin escaping from a few goons who get the drop on him and flagging down the first car that comes by. True to Cunningham form the car is driven by a super-hot young woman named Kristi – a girl who, we’re told, has a “Farrah Fawcett” hairdo. The Penetrator has truly entered the late ‘70s. In the past I’ve been overly critical of Cunningham’s penchant for arbitrarily shoehorning hot women into the lives of his men’s adventure protagonists, but honestly I was missing the point – these books should be escapist fantasies for men, and Cunningham knows what he is doing.

But the wah-wah’d action between Hardin and Kristi never happens…instead the gal treats us to yet another of those Cunningham penchants: the rambling monologue. Hardin ends up sleeping on her couch. He vows to move out asap, because his mere presence could put the girl in jeopardy, but it’s not like he’s in a hurry about it or anything. Indeed, the next we hear of Kristi she answers the phone breathlessly when Hardin calls to check on her, letting him know some men have come over looking for him – and they proceed to threaten her and hang up on Hardin. And what does our hero do? Chalks Kristi up as good as dead and heads on over to the beach to check out the view! (Seriously!)

Kristi isn’t the only girl in the story to suffer harsh torture; Hardin’s girlfriend Joanna Tabler enters the narrative around this point, working undercover. She too is researching Preacher Mann, in some of the laziest coincidental plotting ever. However she doesn’t know Hardin’s down here, and vice versa. So she goes undercover to get a receptionist job at a suspected Preacher Mann front, only for the dude behind the desk to reveal he knows who she really is…a Samoan henchman comes out and strips Joanna down while the dude behind the desk gets up and starts alternately slapping and sucking on her “full breasts.” Then the Samoan takes her to a side room and rapes her!

So as you can see, the lurid, sleazy element missing from Cunningham’s last few novels has returned. The action isn’t as bloody, though; when Hardin stages a mid-novel assault on a Preacher Mann building (the same one Joanna was earlier abducted in, though Hardin doesn’t know this), Cunningham doesn’t dwell much on the gore. Instead he’s more about Hardin’s weaponry and gear, in particular a Resistweve blacksuit that stops a few bullets, “only” bruising a rib or two in the process. Hardin mows through the office building, blasting away with a Mossberg riot shotgun, his ever-reliable dart gun Ava, and some White Phosphorous grenades.

Intel captured in the building raid leads Hardin to a secret island seven miles off the coast of Florida. He has no idea what’s there, just assumes it’s where Preacher Mann is plotting whatever the hell it is he has up his sleeve; Hardin has come across the term “cryo” in the captured papers but doesn’t know what it means. Hardin makes a night reconnaissance on the island and finds it to be a barren, foggy patch of soil. Preacher’s henchmen are beneath the ground, though, as Hardin discovers in a very long sequence in which he takes cover and fights off guard dogs, machine guns, explosives, and even soldiers who pop up out of hidden doors along the island’s main hill.

Busting his way inside, Hardin finds a high-tech complex burrowed into the caverns beneath, all of it quite similar to the later Killmaster novel Deep Sea Death. Here Preacher Mann conducts his cryogenic experiments; Hardin, once captured, is treated to a tour of the facilities per the Bond cliché, and is informed by the muscular, bearded, and bald Preacher Mann that they have not had much success with resuscitating the humans they’ve killed and then frozen. Special mention must be made of the initial Hardin/Preacher meeting, in which Hardin, to bait the Harlem native, starts throwing around the “N-word!” That was pretty surprising to see.

Sadly, the whole “let’s capture women and freeze them” plot is given short shrift; Preacher hasn’t figured out exactly how to do it, and his business model seems a bit skewed. He says something about a problem with the women he steals getting fat, thus he came up with the idea to freeze them, so he can keep them in perfect shape once the clients are sick of them, to be frozen and thawed and shipped out again to the next client. I’m sure there would be much less costly alternatives to this scheme. But already he’s spent a few million on the venture, and he blithely shows Hardin around his SPECTRE-type underworld lair.

Preacher goes one step further by offering Hardin a job, but instead Hardin challenges him to a stick fight(?!), and after a lengthy battle Hardin not only knocks Preacher Mann out but also disarms two shotgun-wielding guards. This takes us into the bloodless finale as Hardin frees Joanna and then sets the place to blow – once the seawater mixes with the leaking cryogenic stuff, we’re told, it will go off like dynamite. Also, Preacher Mann is one of the very few villains in the Penetrator annals to escape, vowing to get revenge on Hardin someday.

Cunningham leaves a lot of stuff unresolved: for one, Hardin never does take vengeance on whoever it was who kidnapped (and killed?) young Kristi, even though he swears over the phone to the kidnapper that he will. And Joanna’s rape is completely glossed over, with the rapist never even being mentioned again, let alone returning so that Hardin or Joanna can dole out some gory payback.

Joanna, reunited with Hardin, doesn’t mention any of her ordeals, and the novel ends with them renting a beach house in Florida and soaking in the sun for two weeks – though Hardin’s already thinking about his next mission, which will have him looking into the dangers of nerve gas.

Thursday, May 14, 2015

The Devil's Kiss (Devil's series #1)

The Devil's Kiss, by William W. Johnstone

No month stated, 1980 Zebra Books

Apparently William W. Johnstone devoted himself to writing for ten years before he finally got published, but reading The Devil’s Kiss you’d think it was more like ten minutes, and that’s with frequent breaks. But what do I know, because this, Johnstone’s first published novel, initiated a stream of a few hundred books published over the next twenty-plus years, with Johnstone still getting published today, even though he’s been dead for over a decade.

This was also the start of an untitled, unnumbered series which apparently has the same plot over and over again: Satan comes to Smalltown, USA, and God’s chosen Warrior blows a bunch of his followers away after debating about it for a few hundred pages. This was of course the exact same plot of The Nursery, which wasn’t part of this “Devil’s series.” But then, it would appear that the majority of Johnstone’s horror novels feature this same plot. If the formula works, why change it? At least, I guess that was Johnstone’s feeling. Either that or he just didn’t give a damn.

Running to 448 pages, The Devil’s Kiss is mostly comprised of exposition-laden dialog exchanges, brief detailings of the sordid shenanigans of a group of Satanists, and out-of-nowhere flashes of sex and/or sadism. Unlike The Nursery it takes a good long time to get going, and it isn’t nearly as over-the-top or trashy as that later masterpiece. But like The Nursery it’s heavier on telling than showing, with a gruff protagonist who acts almost like a reporter, going around his podunk town and basically interviewing every character he meets, with the reader treated to huge dollops of Christian Right sermonizing.

One difference is that The Devil’s Kiss takes place in 1958, but other than occasional mentions of the Korean War or “that new rock and roll music,” the novel could just as easily take place in 1980. What I mean to say is, there’s not really any attempt at capturing the styles of the period; our hero, Reverend Sam Balon, even sports “longish” hair, has tattoos, and acts in every way like the protagonist of a ‘70s or ‘80s novel. But he is a preacher, and here is the biggest drawback so far as The Devil’s Kiss is concerned, when compared to The Nursery; we must read as our reverend of a hero constantly berates himself for his “unChristianly thoughts” and the like. At times it’s almost like a burlier Ned Flanders with a gun.

But Sam, whose last name sounds a whole lot like “Bolan,” was part of the experimental UNPIK detachment in Korea, which we’re informed eventually became the Special Forces. In a vaguely-described backstory we learn that he came here to smalltown Whitfield, Nebraska at the behest of his super-hot wife, Michelle, who eagerly demanded that Sam take this particular parsonage from the list that was offered to him. But over the past few months Sam has noticed a darkness seeping into the little hamlet of Whitfield; in particular church attendance has been dropping across the full Judeo-Christian spectrum (there’s even a synagogue in this supposedly-small town!).

Yes friends, the rapid decline of church attendance is a huge concern of The Devil’s Kiss. In fact it gets even more narrative space and character concern than the murder of the two teens which opens the novel. There’s a fenced-off, notorious woodlands area of the town called Tyson’s Lake, and these kids cross over it one spring night to screw and whatnot, only to find themselves attacked by these sub-werewolves which are referred to as Beasts. They make a gory mess of the boy and intend to use the girl as a “breeder,” but she escapes, finds Sheriff Walter Addison, and tells him what happened…only for the sheriff and his deputies to take turns raping her before throwing her back over the fence to the Beasts!

A few months later and the disappearance of the kids has been brushed under the carpet. Sam begins the first of his reporter-like methods by asking the local police chief about it. Sam will spend the first 300 or so pages of the book driving around Whitfield and engaging various characters in incredibly long, drawn-out conversations. I thought Johnstone told more than he showed in The Nursery, but that was nothing compared to this! Honestly, the reader must be prepared to endure back-to-back sequences where Sam will sit down with some other preacher or priest or gun store owner and engage him in about twenty pages of deep conversation. Repetition is rife.

Another difference with this volume is that Johnstone doesn’t dwell as much on the local Satanists, who were much more to the fore in The Nursery. We only get a few brief cutover scenes to them; they’re lead by Black Wilder, ostensibly the chief professor behind “The Digging,” in which an ancient sculpture is being dug up near Tyson’s Lake. But Wilder is in reality the devil’s agent and is thousands of years old. He has brought with him his minions, and has turned basically the entire town over to the devil, save for a handful – we later learn that there are only 14 Christians left in the population of 2,500. The horror!!

One of Wilder’s top accomplices is none other than Michelle Balon, yet here Johnstone, who is so overly-detailed about trivial stuff, mysteriously drops the ball. I mean, he informs us halfway through the book that Michelle too is ancient, hundreds of years old…yet by this point Sam has learned of “the Mark of the Devil,” which states that if one is touched by the devil or one of the devil’s followers, that person is forever lost. Hence Sam keeps his wife from kissing him or touching him, etc. But, uh, if she’s a few hundred years old, and married Sam because she knew he’d one day be God’s Chosen Warrior (an actual Johnstone title), then hasn’t she already touched him?? Like many times?

Another thing I didn’t like about the Satanists in this one is that Johnstone stresses how dirty and smelly they are; we’re informed over and over again of the stench of Michelle’s room (she long ago moved out of the master bedroom), and when the Satanists get together for a Black Mass Johnstone writes of the “unHoly” smell of their unwashed bodies. I don’t seem to recall any of this in The Nursery; maybe Johnstone wisely realized that overhyping the stench of his otherwise super-hot Satanic chicks sort of ruined the escapist nature of it all. And besides, wasn’t it the pious Christians of the Dark Ages who thought bathing was a sin and thus gloried in their own funk?

But Sam’s sure that Michelle has gone over to the other side, which makes his growing feelings for hotstuff local blonde Jane Ann Burke all the easier to “endure.” For here’s all the “Sam berated himself for his thoughts” stuff I mentioned above; Jane Ann is good and horny for the preacher, and Sam increasingly feels the same for her, but keeps chastizing himself for this due to his being married and being a preacher and all. He’s the first person Jane Ann calls when some deputies try to smash in her door and rape her, though. Sam insists she move in with gun store owner Chester and his wife, and then returns to his impromptu interviews with the other Christians in Whitfield.

Two of the elder preachers in town, Reverend Lucas and Father Dubois, actually fought the devil years before, and they impart their wisdom to Sam and his reporter friend Wade (as well as Miles the Jew, whom Johnstone assures us is okay even though he isn’t Christian) in one of the longer conversation sequences. Here’s where Sam learns, about 200 pages in, that he’s likely been chosen to be God’s Warrior, and his mission will be to KILL EVERYONE. This in itself is hilarious, as Sam instinctively knows that he should not try to save any of the Satanists, that death is the only option for them. Kind of flies in the face of the entire concept of Christianity – wouldn’t a true Christian try to save their souls?

But nope, the only thing to do is load up on guns and ammo. (Actually, if history’s any indication, that is in fact a valid Christian response!) There’s a goofily maudlin scene where Sam and the others exchange crosses with Dubois and Lucas (they even give one to Miles the Jew!!); you can almost hear the saccharine choir on the soundtrack. Now it’s killin’ time! Oh wait, no it isn’t…we still have another 250 or so pages to go. No, it’s actually time for more discussion and impromptu interviews. Oh, and Sam trades in his car for a pickup truck. Humorously enough the used car salesman is also one of the last Christians in Whitfield.

All too infrequently Johnstone will cut over to Black Wilder and his fellow devil worshippers. We get a Black Mass sort of deal where they have a big ceremony in the fields at night, orgying and whatnot, culminating in a teenaged virgin (who refused to join them) being trussed up on a cross and gutted by Nydia, the raven-haired beauty who serves as Wilder’s chief aide. But again the unholy eroticism is ruined by the focus on the unwashed, smelly bodies of the Satanists. Also this time Johnstone doesn’t dwell on graphic sexual description, as in The Nursery. We’re just informed that lots of screwin’ occurs, including, gasp, homosexual stuff, which is the biggest sin so far as the still-Christian locals are concerned.

The hypocrisy of Johnstone’s vision is laughable; throughout the novel Sam condemns the devil-worshippers, or “Them,” as he soon calls them, because “[their] god says hate Christians.” And yet, Sam himself hates the devil worshippers so much that he relishes the opportunity to murder them: man, woman, and child. There is no attempt at mercy or salvation; even though he learns that the residents of Whitfield are under mind control, and perhaps not fully responsible for the evil beings they are becoming, Sam has no interest in saving them. Indeed, God basically tells him through his subconscious to forget about it. And even in death they won’t be saved; they’re going straight to hell.

Also of note is Johnstone’s view of women. I don’t want to be the cliched modern reviewer who whines about “misogyny” and the like in old pulp fiction. Actually I think these now-outdated sentiments are part of the charm of these old books. But good grief Johnstone goes way beyond that and into a sort of Cro-Magnon realm; I lost track of the number of times Jane Ann or one of the other Christian women would sit quietly while Sam and the men were talking, only to finally get up and say, “I’ll go make us some sandwiches.”

Interesting then that the women are much more visible and important in the world of the devil worshippers. Nydia as mentioned is Black Wilder’s chief aide and takes central stage in the midnight ceremonies, sacrificing victims and lusting after new male (or female) conquests. Johnstone doesn’t outright state it, but it’s obvious that, per his skewed reasoning, this female empowerment is also part of what makes the Satanists so evil and so against God’s will. To prove this there comes a scene midway through where Sam finally attempts to do something about Michelle; finding her masturbating in her foul-smelling room, he pulls her into the shower and then calls over Father Dubois for an excorcism.

Bringing to mind the much superior (and much trashier) scene in The Nursery where the sodomy-lovin’ teenaged gal was called back to Jesus, here we have a similar sequence where a nude Michelle, tied down to Sam’s bed, curses God and spits at Sam and Dubois as they try to save her. But forget it – she’s too far gone, practically a vampire. Or something. Johnstone is vague, but Father Dubois, who has suddenly become Sam’s spiritual warfare advisor, states that the only option is a stake to the heart! After which they dump her corpse over the fence at Tyson’s Lake for the Beasts to eat.

This of course leads to more talking. Even when Sam, Chester, and Wade take up guns and make a sortie over the Tyson Lake fence, even there they engage in a long conversation. Here Johnstone just pulls out any idle thought from his head; we’re informed, for example, that there’s a nearby asylum which is filled with mutants, the radiation-twisted freaks of some nuclear test ten years ago. Sam and his buddies then shoot a few Beasts and talk about it. Then they go home and talk about it with the rest of their companions.

Then Sam finally decides to screw Jane Ann, right out in “the cheap showiness of nature,” to quote Rev. Lovejoy, and then what the hell, he officiates their own impromptu marriage. Around about this time Sam has suddenly started to realize he will die in the conflict, but his child will continue the war against the devil(?!). This seemingly spur-of-the-moment decision on Johnstone’s part comes increasingly to the fore in the narrative. But anyway he and Jane Ann have to be married as part of this last-moment prophecy, or something.

The final 200+ pages are given over to a days-long battle Sam and his followers wage against the devil worshippers of Fork County, which has been magically segregated from the rest of the world. There are many and frequent scenes of Sam gunning down Beasts and human worshippers with his Thompson submachine gun, Chester blasting away at his side with a Greaser. Johnstone doesn’t get very outrageous with the gore, though, and these “action” scenes get boring after a while, as there’s no variety to them. The Beasts and Satanists just rush pell-mell at Sam and his followers, who gun them down, and then mop up the survivors.

Johnstone loses track of all the stuff he’s spent a few hundred pages setting up…those asylum mutants, for example, show up and are anticlimactically blown away within a single paragraph! Long-time Whitfield residents are summarily killed by Sam and his cronies, and though Sam et all are shocked we readers have no idea who these characters are in the first place. Much better are the close-quarters moments where Sam will take a sharpened stake and go in some dark area to kill off one of the Undead, which are basically vampires. Johnstone has the glimmerings of some actual eerie stuff with murdered companions returning as zombie/vampires, but does nothing to capitalize on it.

As mentioned the “certainity” that Sam will die in the climax is further brought the fore, as well as a last-second development where hotstuff witch Nydia vows that she will sire a son through him. Johnstone, certain that he’ll get a contract for a sequel, introduces this concept that Sam will have a “good” son through Jane Ann and a “bad” son through Nydia, and they will fight each other thirty twenty-some years in the future. God unsurprisingly isn’t much help (he’s mysteriously absent whereas Satan is constantly beaming messages to his loyal followers), so Sam basically gives Jane Ann a goodbye kiss and goes off to meet his fate.

Johnstone doesn’t get as graphic in the infrequent sex scenes as he did in The Nursery, and for the Nydia/Sam encounter he doesn’t elaborate at all, yet ironically enough it features the best writing in the entire damn book. In fact Sam’s final moment has all the emotional power Johnstone has been trying to build over the entire endurance test of a novel, as Sam goes off to meet his God knowing somehow that he will have a son, a son that God will look over (which, judging at least from how the Christians are treated in this particular book, doesn’t really mean much).

In the end, Whitfield is in ruins, Sam and his companions having blasted most of it using handmade napalm (gasoline mixed with flour) and dynamite. Practically everyone is gunned down, the dozen Christians having killed a few thousand people. As for Black Wilder, he blithely gives in to his doom, having been ordered by Satan to give up, but Johnstone implies that the demon may return. Another potential return in the next volume would be a teenager named Jean, the only Satan worshipper who escapes Sam’s bloodbath; we’re informed that she eventually gets a job as a Government-sponsored psychiatrist (surely there’s yet another Johnstone-worldview message there).

Three years later Johnstone returned to the storyline with The Devil’s Heart, which brought events to the then-modern day, and apparently started off a series of four more books featuring Sam Jr. and his ceaseless battles against Satan. Once I have recovered sufficiently I will read it.

Finally, here’s a funny story Stephen Mertz told me, and with his permission I’d like to share it with the rest of you:

I met [William W. Johnstone] once. A biker buddy who enthusiastically collected his work once dragged me down to a book signing. Johnstone was on tour, promoting his Ashes series and he actually had two uniformed, armed off-duty cops with him, hired to stand in the background at the Hastings store as "security." (!?)

We chatted briefly and traded signed copies. I couldn't help myself. I nodded toward the cops. "What's this, Bill? You expecting the critics to show up?"

This brought a semblance of acknowledgement from a generally dour, guarded countenance.

Monday, May 11, 2015

The Twilight Strangler (Airport Cop #2)

The Twilight Strangler, by Charles Miron

No month stated, 1975 Manor Books

First of all, thanks to Justin Marriott for bringing this obscure, three-volume series to my attention. But then, judging from the dearth of information and reviews on the web, it doesn’t look like too many people have heard of it. All I know is that Charles Miron was a real person and published a handful of novels through Manor Books, this being the only series.

Typical of other Manor series books of the day (like Kill Squad), there are no volume numbers: Airport Cop was the first one, The Twilight Strangler was the second, and Death Flight was the third and final volume. I don’t have the first volume, but if this second one’s any indication Airport Cop is one weird “action series” indeed.

My friends, I may have found another Gannon here, at least so far as the bizarre writing style goes. To be sure, The Twilight Strangler is nowhere as nutzoid, violent, or extreme as anything in the Gannon novels, but it is written in a somewhat-similar screwed-up style. As with Dean W. Ballenger, you wonder if Miron was writing this way purposefully, sort of how Ballenger proved he could write straight narrative in his standalone WWII novels and his men's adventure magazine work.

But then, if this is the way Miron naturally writes, the guy is definitely on a different wavelength. The Twilight Strangler reminded me mostly of that psychedelic “crime thriller” I reviewed a while back, Mystery, only without the fantastical elements. But style-wise it’s very similar, with the characters seeming to exist in a world that is only tangentially related to the book itself. The reader is thrown in and must fend for himself as the author hopscotches perspectives, situations, settings, even time periods, sometimes within the span of a sentence.

For example, I read the entire novel and I still don’t know if the titular airport cop, Verban, even has a first name, let alone what sort of cop he is. The back cover states he’s “chief of airport security,” but that doesn’t seem to be the case in the book itself. In fact it seems like he’s a regular cop, one who possibly specializes in airport crimes. For that matter, it wasn’t until page 60 that I got confirmation that Verban was based out of New York; before that I honestly couldn’t tell if it was Los Angeles or NYC. Actually Verban is identical to the type of cop protagonist you’d meet in one of William Crawford’s novels, and the novel is just as mired in police-world details.

But The Twilight Strangler is almost psychedelic in how it hopscotches across perspectives and situations, Miron never bothering to set up or explain anything; it’s almost the men’s adventure equivalent of Rudolph Wurlitzers’s Nog. I’ve complained before about “POV-hopping,” where an author changes character perspectives without warning the reader through a chapter break or a few lines of white space: Charles Miron takes this to a whole different level, with POVs sometimes changing within the same sentence. Before I read this novel I would’ve said such a thing would be impossible, that every writer would know not to do this. But Miron proved me wrong.

So anyway, Verban, sometimes called “Verb” by his partners, is a New York cop who apparently works the airports. There’s absolutely no description of the character, so I guess the cover painting will have to suffice. When we meet him he’s already on the case; in the first of the novel’s brief murder scenes, a highfalutin model is strangled while shooting a commercial in an airport (I think it’s at JFK, but I never could figure out for sure). Verban is put on the case by his superior, Captain Kinsella, and works it with his new partner, a black cop named Reggie Wasson who is trying to fill the shoes of Verban’s regular parner, Freddie Karp, who is on vacation but returns later in the novel.

There’s also a “policewoman” in the crew, Candace Reuscher, and she serves more as Verban’s partner (both on the streets and in bed) than any of the other characters. Also it must be mentioned that Miron has no qualms with referring to his characters by multiple names in the narrative; it took me a few pages to realize that Wasson’s first name was Reggie, for example. Just like in a William Crawford novel we get a lot of immaterial stuff where these cops brainstorm who the killer might be, going out and tracking down leads, even checking their files for potential suspects.

All this stuff is pointless because we readers already know who the killer is, and he’s not on any of Verban’s lists. His name is Milo Kline, and he is a reclusive sadist who reminded me for all the world of Ignatius Reilly in A Confederacy Of Dunces. He has the same pretentious, stentorian tone and everything. However I couldn’t figure out if Milo was skinny or heavyset, or ugly or handsome; he seemed to be described either way. Why he gets his jollies strangling women is never explained, but he does have the arrogance of Ignatius, thinking of his victims as “immoral women” and etc, so I guess we’re to infer he’s just wiping them out for the betterment of the world or something.

Milo also likes to strangle with antique tools – a barber chair strop, an old hemp cord, even the antenna of a ‘40s television set. This is something which eventually has Verban hitting the antique stores in Manhattan, tracking the guy. A yet another unexplained subplot has Milo calling Captain Kinsella to taunt him before each kill. The murders aren’t limited to New York, with Milo flying around to different aiports to murder various women, among them a lesbian fashion designer, a stewardess, and even a teenager. In almost each case we get several pages from each woman’s perspective, hopscotching around their thoughts with no concern over plot or narrative structure. All of it of course rendered moot when the woman is dead and never mentioned again.

After the “twilight strangler” (so called by the cops due to his penchant for killing at this time) taunts Kinsella that he’s going ot kill someone at Chicago’s O’Hare aiport, Verban goes “off duty” and flies there on his own time, Candace accompanying. Miron builds up a rapport between the two which takes the expected route, though our author is very shy when it comes to actual sex scenes (nevertheless, characters will often reflect back on whopping orgasms they’ve had, in those wily-nily flashback POV sequences). They butt heads with the O’Hare chief cop and, worse yet, find that the Strangler’s struck again, despite their efforts. This gets Verban thrown on a week’s unpaid leave; he uses the time to scout out those antique shops.

The novel gets even more bizarre when Milo goes on vacation(!?) in the Caribbean, where he’s hit on by this hotstuff divorcee who has become a millionaire thanks to her ex-husband; her name is Elyse and she talks like a Bringing Up Baby-era Katherine Hepburn. She takes an immediate sexual interest in Milo, demands he come back to her hotel with her, and further announces they’re to be married(!?). Milo acts again like Ignatius Reilly throughout, fending off her advances and protesting how forward she is. She sticks around for a long time and, surprisingly, does not get killed by Milo, who instead finally manages to “escape” from her several weeks later.

But this is another of those pulp novels where so much time is wasted on inconsequential stuff that the climax is hurried. For example, we could’ve done without a lot of the stuff in the middle half, like Milo’s ordeals with Elyse, or the arbitrary part where Verban just happens to stumble upon an auto theft ring (mirrored in a later scene where Candace stumbles upon a pickpocket). These parts do offer a little action – and Miron doesn’t exploit the violence at all, in fact I don’t think you even read about a single drop of blood in the entire novel – but they ultimately come off as chaff, especially when you consider how abrupt the finale is.

In short, the “climax” occurs over the span of a mere two pages; using Candace as strangler bait, Verban and team scout JFK airport and manage to put the hammer down on Milo just as he’s knocked out the girl and shoved her into back of a Jaguar. Milo slams into Verban’s partner Karp as he speeds away (we never do learn if Karp lives or dies) and Verban gives chase in a Dodge Charger. Half a page is left. Comedically, without the event even being described, Verban is somehow magically able to teleport himself out of his car and onto the hood of Milo’s Jaguar! Like a regular TJ Hooker he manages to pull Candace free as the Jaguar plunges into the Hudson.

And that’s that! We’re informed Milo’s corpse is eventually fished out of the river, but there’s no wrapup or anything. We never learn why he was on his kill-spree or how he even knew who Captain Kinsella was. But while the writing style was unusual and the action sporadic and flimsy, I can’t say The Twilight Strangler was terrible. It had a weird sort of appeal, like an ugly dog you can’t help but keep staring at.

Also Miron has a definite gift for dialog, with the characters trading banter with aplomb. The minor characters sort of spring to life, in particular a kid calling himself “The Big E” who shows up for a single page and steals the entire novel; he offers legal counsel when Milo falls while running along a beach on vaction. I could’ve read an entire book about that kid. Anyway, I have Death Flight, which appears to be about hijackers, so eventually we’ll find out if it’s written in the same sort of impenetrable style.

Thursday, May 7, 2015

The Fast Life

The Fast Life, by Cynthia Wilkerson

No month stated, 1979 Belmont Tower Books

The second of two novels Len Levinson wrote as Cynthia Wilkerson, The Fast Life is nothing at all like its predecessor, Sweeter Than Candy. Whereas that earlier novel was a sleazy yet goofy tale of a Manhattan-based harlot, this novel is more akin to a category romance, or at the very least something like Jacqueline Susann might’ve written. It’s also longer than the average Belmont Tower book of the day, coming in at only 318 pages but with fairly small print.

Like Sweeter Than Candy, The Fast Life features a female protagonist, but this novel is told in third person. Our hero is Roni Woodward, a 22-year-old blonde knockout from Savannah, Georgia who has just graduated college and is taking a leisurely tour of Europe with her wallflower of a cousin. On the first page of the novel Roni is in Paris and meets Chaz Razzoni, an Italian in his 40s who is internationally famous as a Grand Prix racer, though Roni has never heard of him.

Chaz is described as a sort of European dandy, a veritable greasy lothario, but he has his European ways with women and Roni, despite herself, feels drawn to him. He promptly begins hitting on her; the first several pages are comprised of their first conversation, in a café on the Champ Elysees. Chaz for his part feels drawn to Roni, and not just due to her stunning looks and awesome boobs. He senses something different about her, a fire burning within her that is much like his own. She’s also, he later professes, just as self-involved as Chaz himself is.

I might not be an internationally-famous sports celebrity or an Italian lothario, but I am around the same age as Chaz, and I at least would know that Roni spells nothing but trouble. When Chaz picks her up in his Guastalla 450 GT (Guastalla being the Lamborghini-like manufacturer Chaz races for) for their first date, Roni claims that she used to drive her now-dead brother’s stock car, back in Georgia, and says she wouldn’t mind driving Chaz’s car. When Chaz doubts her skills, this leads to a huge breakdown on Roni’s part, demanding that Chaz let her out, even grabbing hold of his wrist and tearing into him so savagely that she draws blood.

At this point I would’ve hooked a U-turn and dropped her ass back off at the hotel.

But Chaz shrugs it off and indeed feels bad about it. Wanting to get this off their collective chests as soon as possible, he forgoes the party they were headed for and instead takes Roni to a nearby racetrack. There he allows her to take his Guastalla for a few spins around the track. One thing to note about The Fast Life: unlike the other novels I’ve read with racing protagonists, such as the Don Miles and The Mind Masters books, this book actually does have a lot of racing stuff in it. In fact there are racing scenes that go on for several pages.

The first quarter of the novel documents Roni’s introduction to the European jet set of the mid ‘70s. (Interestingly, we aren’t informed until page 212 that all of this is occuring in 1974, the same year as a few of Len’s other books, for example The Bar Studs and Bronson: Streets Of Blood.) She instantly butts heads with most of them, in particular the Countess to whose castle Chaz takes her to on their first date. Here also Roni meets other characters who will gradually become important in the narrative, in particular Bobby Barnes, a 23 year-old American Grand Prix champion who races for a British team, and Gilles Cachen, a mean-looking Frenchman who races for Guastalla.

Roni’s brother Allan was as mentioned a stock car racer, and died in a wreck; Roni due to this (and other reasons) has kept herself from being interested in racing or from letting herself go and enjoying life. But Chaz opens this world back up for her, and she finds that she still wants to race, especially after driving his Guastalla. And after, uh, driving Chaz himself (in the first of the novel’s few graphic sex scenes – which by the way are nowhere as sleazy and explicit as in Sweeter Than Candy), Roni not only becomes Chaz’s new woman but also talks him into letting her drive one of his starter race cars.

Living with Chaz now outside of Rome, Roni competes in the Formula Junior race, which is open mostly to youngsters and women – we are reminded quite often that there are no female Grand Prix racers. Roni, driving aggressively and skillfully, wins the race, and is dubbed the “American Eagle” by the press. (This is a world by the way where junior races in Europe are reported on in Georgia newspapers, and Roni’s shocked and worried parents immediately become aware of her newfoud fame – and proceed to nag her to come home.) But this isn’t enough for greedy Roni, who insists that she should be given a chance to be on Chaz’s Guastalla team, and to race against professional drivers on the Grand Prix circuit.

Chaz for his part is so smitten with Roni that he basically evangelizes for her with his superiors at Guastalla. Unsurprisingly, they’re not interested – the girl, after all, has only won a single race in her life! But Chaz, who hasn’t had much success in racing lately, decides that if he wins an upcoming race he will be so “hot” that Guastalla will have no choice but to give in to his demands…especially if he threatens to quit. This is exactly what happens, Len turning out another long racing sequence. Oh and I forgot to mention – Chaz brings to mind other ‘70s Levinson protagonists, picking himself up a healthy cocaine addiction in his determination to win the race at any cost.

In fact this coke frenzy is what serves to drive an eventual wedge between Chaz and Roni, as a cocaine-numbed Chaz becomes increasingly withdrawn, distant, and uninterested in sex. He’s now a champion again and can think only of racing. Roni meanwhile gets her wishes fulfilled with a contract with Guastalla, the president unhappily caving in to Chaz’s demands, though she soon finds out that they plan to treat her as nothing more than a public relations prop. But Roni insists that she’s to be treated like a “real” racer and puts in serious time on the track with Giuseppi, the man who claims to have coached Chaz to greatness. As the novel progresses, Chaz fades more to the background and Roni becomes our sole protagonist.

As far as protagonists go, Roni is kind of…well, I’m not sure what to think of her. She is for the most part unlikable. “Self-involved,” “irascible,” “incapable of loving anyone but herself;” these are just a few of the ways she’s described by the other characters (and sometimes by herself). Yet she’s too multidimensional to just be disregarded as an unlikable character. She shares the same goal-oriented mindset of most every other Len Levinson protagonist, determined to storm her way through life and go for the gold. Yet at the same time she misses that spark that makes Len’s other protagonists so likable; even Len’s version of Joe Ryker in The Terrorists was more likable than Roni.